COVID-19 and the ensuing preventative measures has caused a rate of Economic downturn akin to the great depression. Whilst on virtual work experience with Delta 2020, Jack Thorpe Yr13 Kingston Grammar School student aimed to assess the damaging consequences of a economic shutdown on the job prospects of today's youth.

In the 10 weeks since the WHO’s announcement of the COVID-19 global pandemic and the ensuing safety measures taken to avoid unnecessary deaths, the UK economy has been facing one of its largest challenges to date. I believe that, while generally shielded from the virus’ symptoms, the UK’s youth, particularly those set to leave full time education, will take the lion’s share of the economic downturn in the form of high unemployment.

As a former bartender, now unemployed due to the pub chain entering administration during the COVID-19 outbreak, I have experienced this turmoil first hand. Using the 2008 financial crisis for reference, as well as current predictions for the UK economy’s trajectory, we can analyse the likely outcome for certain age-groups, while considering gender and other socio-economic factors.

With the UK’s Gross Domestic Product now down 2 percentage points as of March 2020, as recorded by the ONS, the economic theory of the negative accelerator process suggests that companies will cut back on investment projects and expansion in anticipation of future decreases in aggregate demand. As seen in previous recessions, entry level jobs tend to be first on the chopping block due to the necessary training needed to reach a level of productive efficiency required for profitable returns. After reaching a trough of 432,000 vacancies, post financial crash in April-June 2009, the current economic downturn seems to be following suit with a significant drop of 170,000 vacancies since the last quarter. While I luckily retain a 3-year buffer to spend social distancing at university, this poses a serious conundrum for those currently leaving full-time education with various levels of qualification.

Recent research by the Institute of Student Employers claimed that entry-level jobs have been reduced this year by 23%, destroying the first rung on the employment ladder many leavers were hopeful to climb. Furthermore, unlike previous recessions, sectors worst affected by the outbreak, including hospitality, travel and non-food retail, have been temporarily shut down and face an unprecedented level of uncertainty regarding when and how business will be allowed to continue. Unfortunately, these sectors attract a large proportion of 18-24-year olds, with one in five graduates and one in three non-graduates finding themselves applying for jobs in a now shutdown sector.

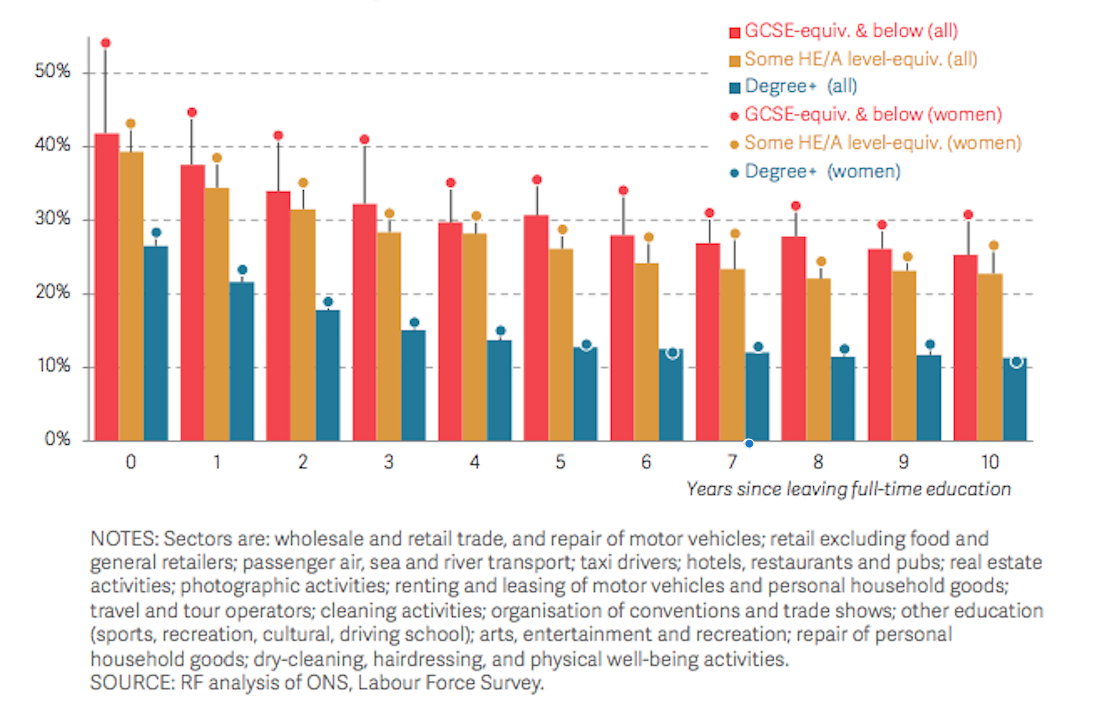

With an estimated 800,000 full-time education-leavers already facing the insurmountable task of navigating this depleted labour market, students leaving with only GCSE level qualifications seem to be in the worst situation of all. After enduring a 10-percentage point hike in unemployment compared to a rise of only 3.3 percent in general unemployment, between 2007-2011, employees recently having left education with GCSE level qualifications are in pole position to receive the dreaded P45 this time around. Particularly worrying is the number of young women with qualifications limited to GCSE who are heading into now shutdown sectors. The graph found below, produced by the Nuffield Foundation, shows a larger proportion of non-graduate leavers begin their careers in shutdown sectors.(5) Averages taken suggest over 50% of young woman, after leaving school, would have been heading into sectors now shutdown due to COVID-19 preventative measures. While this may have a short-term damaging effect on the employment differentials between genders, I believe it may have hidden benefit as young woman choose to remain in education, potentially leading to a decrease in the wage gap between men and woman later on. For those lucky enough to find or retain a job, the Nuffield Foundation predicts significantly lower pay, 19 percentage points lower than if unemployment had not risen, for students leaving with low-level qualifications.

Graph reproduced from the Nuffield Foundation [Class of 2020, Education leavers in the current crisis, Kathleen Henehan, May 2020]. Proportion working in coronavirus shutdown sectors, by number years since leaving full-time education and highest qualification held: UK, 2009-2009.

While the situation is dire, every cloud has a silver lining. With an increasingly unpredictable labour market, students may choose to remain in the stability of education, honing their skills to increase their human capital and consequently their employability. With a relatively lower opportunity cost of studying rather than working, the universities must now act fast to improve flexibility of their admissions process, to adjust for late applicants who have changed their mind. Thanks to a demographic dip in the birth rate the late 2000s, the current cohort making this decision is relatively small and therefore universities can help a larger proportion of applicants. Universities are also able to offer more spaces previously filled by foreign students. Not only would a three-year buffer increase employment chances by almost 50%,(5) but a degree-level qualification would also provide education leavers with wider occupational mobility to traverse any COVID-19 related demand-side shock. In previous recessions, enrolment in higher education has significantly increased, exemplified by a 7% increase in education enrolment in 21-23-year olds between 2008-2009.(5) Contrary to trend, medicine entry level jobs are likely to increase due to the pandemic. This factor combined with the heroic efforts of front-line NHS staff may inspire a generation of medics from all backgrounds.

As young people in the UK stave off the boredom, perhaps contented by the palpable environmental improvement during lockdown, serious thought must be given to their future prospects. While Sweden have seen a higher death rate than its Nordic neighbours, their policy of no lockdown could perhaps give them, and consequently their youth a head start once the pandemic ends.

While inclined to only consider paths of self-preservation, the young must also not forget the real victims of this tragic pandemic. With the UK death toll, at the time of writing, at just over 36,000, the UK’s elderly face a solitary existence, made worse by the volatility of pensions linked with the unstable stock market. With the Office of Budget Responsibility now warning GDP could fall by 35%(6) in the coming months, questions should be raised about the restrictions that have been placed on the economy. But also, another question needs to be answered – How much is a life worth to you?

Jack Thorpe

Kingston Grammar School

Sources

1Office of National Statistics. GDP first quarterly estimate, UK: January to March 2020 https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/grossdomesticproductgdp/bulletins/gdpfirstquarterlyestimateuk/latest

2 Office of National Statistics. Jobs and vacancies in the UK: March 2019

3 Office of National Statistics. UK labour market 19 May 2020 https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/articles/coronaviruscovid19roundup/2020-03-26#labourmarket

4 Industry of Student Employment. Press Release, 18 May 2020. Employers cut entry-level jobs by 23%

5 Nuffield Research Foundation. Class of 2020. Education leavers in current crisis. Kathleen Henehan. May 2020

6 Office Budgetary Responsibility. Coronavirus analysis May 2020. https://obr.uk/coronavirus-analysis/