Whilst on work experience, Year 10 student Malachai Jacobs from the Bishop's Stortford High School wanted to delve deeper into the history of Virtual Reality, as this disruptive technology has deeper roots than one would initially think. Here we share his article:

Believe it or not, Virtual Reality (VR) has been around since 1968, when computer scientist Ivan Sutherland created the first head-mounted display. Many would hear the phrase “VR” and think of the hardware prevalent in 2016, such as the Oculus Rift or the Samsung Gear headset, but the head-mounted display (HMD) is in fact a piece of technology that has existed for nearly fifty years prior to its recent hype. In 2018, Gartner removed VR from its hype cycle, saying that it is “rapidly approaching a much more mature stage” and that it is no longer an emerging technology.

So how was VR first conceptualised? And how much has it changed since 1968 when Ivan Sutherland and his student Bob Sproull created the Sword of Damocles, starting the long journey down the road of Virtual Reality, or when the idea of creating a false reality that a user can interact with or view was formed?

Virtual Reality During Pre-20th Century

To start I would like to go further back, past 1968 and look at what the Virtual Reality Society views as some of the early attempts at Virtual Reality. Were you to take the phrase “Virtual Reality” literally, you would be left with this: a way to create the illusion of a place, object or experience that doesn’t actually exist in the physical world. In this way, some paintings achieved that very effect. In the nineteenth century, artwork known as panoramic paintings – such as the Battle of Borodino 1812 Panorama – was made. These types of paintings surrounded the viewer and gave the effect of feeling like you were present, especially due to the full-size foreground. So not only was a Virtual Reality headset made before 2016, but the idea of immersing oneself into a virtual environment has existed for hundreds of years.

In 1838, Charles Wheatstone produced some research, which demonstrated how the brain could process information consisting of two different two-dimensional images from each eye and transform it into one image with three dimensions. This effect could be achieved through the use of a stereoscope and would allow people to view pictures in a way which one wouldn’t normally be able to see them. Later, after Sir David Brewster’s improvements that made the contraption portable, you would be able to see your surroundings in this way: thus, creating a Virtual Reality.

This same principle is still used today, whether it is in the Google Cardboard, or other cheap VR headsets. These devices use simple designs that place your device the optimal distance from your eyes and display the two images separately, creating the 3D effect.

Virtual Reality During the 20th Century

Moving towards and past the millennium, virtual simulations were used in more innovative and different ways. In 1929 Edward Link created the “Link trainer”, which was the first flight simulator, and trained over 500,000 pilots during World War II. This was the first notable example of how a variation of VR could do good for society.

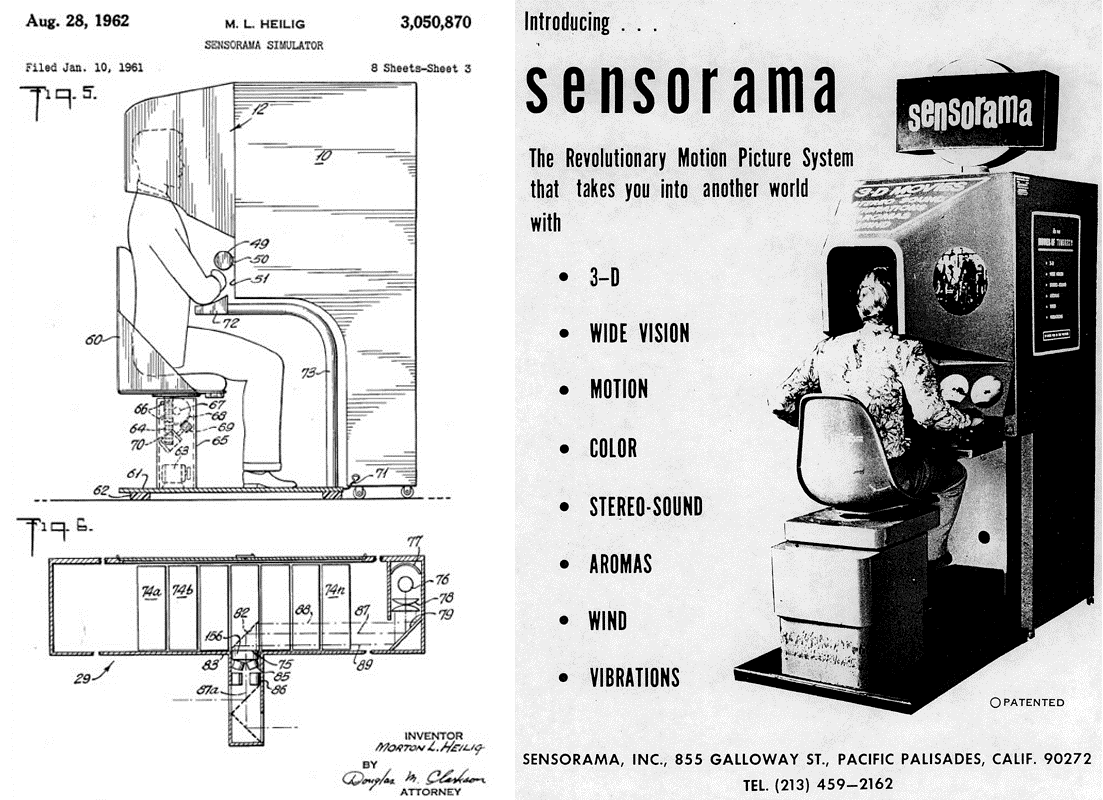

The next major step towards VR was in 1957 with Morton Heilig’s Sensorama: an “arcade-style theatre cabinet”, which contained aspects that stimulated all senses, for example a stereoscopic display, fans, speakers, and even a vibrating chair. This culminated into an experience that would fully immerse the user into the film they were watching.

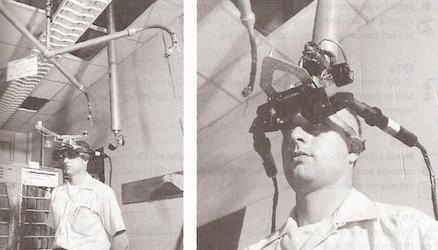

This was closely followed by his head-mounted display, albeit without motion tracking, in 1960, and then Comeau and Bryan’s first motion tracking HMD in 1961. Despite neither of Heilig’s inventions materialising during his lifetime, they set a precedent for what was to come for VR and laid the groundwork for the future technologies of VR, most notably the Sword of Damocles.

And thus in 1965, Ivan Sutherland created the concept of the “Ultimate Display” – a reality so authentic that you could not tell the difference between it and actual reality. The description included a virtual world viewed through a head-mounted display, the ability to interact with the world realistically, and hardware that could create and maintain the virtual world in real time. He said this about his concept:

“The ultimate display would, of course, be a room within which the computer can control the existence of matter. A chair displayed in such a room would be good enough to sit in. Handcuffs displayed in such a room would be confining, and a bullet displayed in such a room would be fatal. With appropriate programming such a display could literally be the Wonderland into which Alice walked.”

The development of the concept of VR had reached the speed at which new innovations were being made each year, and this continued through to 1968, when the first VR/AR head mounted display which was connected to a computer, not a camera, was created: The Sword of Damocles. The user would have to be strapped into this device, which hung from the ceiling due to its weight. Despite the graphics not being anything like what we see today in modern VR, this was an innovation which merely ten years before would seem preposterous.

From that point forward, the development of VR modernised rapidly. Just one year after Sutherland’s invention, Myron Kruegere developed several experiences which he named “artificial reality” – this eventually led to the VIDEOPLACE technology, which let people interact, despite being miles away from each other: a technology that now is found in most devices and software.

However, at that time, people still didn’t know what to call Sutherland’s innovation. That changed in 1987 when Jaron Lanier coined the term “Virtual Reality”. Lanier and his company sold several products in the Virtual Reality market: the EyePhone 1 (for $9400), the EyePhone HRX (for $49,000) and the Dataglove (for $9000). The technology was very expensive and unnatural: it was uncomfortable to wear and silly to look at. As well as this, the frame rate of the simulation was still extremely low: at around 5-6 frames per second – a terrible rate compared to the 30 frames per second which the television sets at the time were running at. Furthermore, on top of the cost of the EyePhone system, the computers required to run it were also exorbitant. The total cost of the entire set was upwards of $250,000. This meant that few could afford or had interest in the technology, and so investors also started to lose interest and moved towards the field of mobile technology.

The widespread growth of VR

In 1990 Jonathan Waldern exhibited Virtuality, a VR arcade machine, at the Computer Graphics 90 exhibition in London. The next year, the Virtuality Group launched Virtuality. Users could play in a 3D gaming world using these arcade machines. They were the first mass-produced entertainment system that featured VR, and users could even connect them together to play multi-player games with less than 50 milliseconds of latency. Even popular arcade games like Pac-Man had VR versions.

As well as this, SEGA announced that they were working on their own VR headset that would be available for purchase by the general public: something the world hadn’t seen yet. It was meant to be used for arcade games and the Mega Drive console, but it was never released, despite having four games made for it.

Instead of releasing the headset, they released the SEGA VR-1 (an arcade machine) in 1994.

The next year Nintendo released the Virtual Boy console, which was the first portable console to display 3D graphics, however it failed and was discontinued a year later due to the lack of colour in its graphics and the discomfort users felt whilst using it.

Virtual Reality in the 21st Century

In 2007, Google introduced the Street View feature in Google Maps. Three years later, a stereoscopic mode was added to this. That same year, Palmer Luckey created the first prototype of the Oculus Rift – a well-known brand of VR headset today. It featured a 90-degree FOV, which hadn’t been done before, and refreshed the interest in VR globally.

In 2012 Luckey launched a Kickstarter campaign for the Oculus Rift, and it raised $2.4 million. Facebook went on to purchase his company for $2 billion just two years later, and thus began the momentum that VR has gained since then. Many companies announced their own VR projects – for example Google with the Google Cardboard, Sony with their Project Morpheus and Samsung with their Samsung Gear VR.

Modern uses of VR

Virtual Reality, although a source of great fun, has also benefited many in other ways. VR is used in many areas of healthcare, ranging from diagnosis to treatment and it can be used in surgery, rehabilitation and counselling. For example, VR was used to create war zone scenarios for Vietnam veterans receiving exposure therapy for their PTSD, and to take terminally ill patients on journeys in VR.

Furthermore, VR is used as a means of training medical professionals by allowing the students to interact with the human body to learn and understand it better. It works better than testing on real humans because mistakes can be made without hurting or permanently damaging the patient and they can be reversed.

VR can be used to educate patients about making positive and productive lifestyle choices, by teaching them about the effects of smoking or the overuse of alcohol.

VR has also been used in counselling. An example of this is phobia treatment, where the user is placed into an uncomfortable environment and can face their fears and build up their confidence.

It is used in design and testing – many of the products that you use in your every-day life may well have been tested in a virtual environment, allowing simulation to test safety or viability.

VR in the future

So where will VR go in the future? Many think it will be the successor of the smart phone, and others think it will lose its hype and be fitted among the many niches of technology that exist today. Oculus have announced that they see a future of ultra-thin headsets, indicating that VR’s future is hopeful. Personally, I hope that VR will become more accessible to everyone, and more people will be able to experience what it is like to be in a virtual world. You might imagine a world where everyone spends most of their life in a virtual world, but I’m not so sure that that is feasible nor the direction in which we are going. I think that the VR companies will start working on making more portable, usable devices which we can use more frequently and comfortably, making both the experience and the accessibility better.

One big problem with VR is the Virtual Reality sickness that people experience when using it. The technicalities behind the cause of this are unknown, however the consensus is that it is due to the disparity between what happens in the real world and what happens in the virtual world. This can range from moving in VR while not moving in real life to latency issues, causing many symptoms such as disorientation, nausea or fatigue. Former Oculus scientist Steven LaValle says, “Every time you grab onto a controller, you’re creating motions that are not corresponding perfectly to the physical world. And when that’s being fed into your eyes and ears, then you have trouble.”

One step in the future of VR will be to fix problems like these permanently. Some solutions include introducing a static frame of reference, whereas others involve reducing things like the field of view and rotational movement. One unique solution was MONKEYmedia’s BodyNav innovation: a development which removes the system of movement through a controller, and instead uses body movement to move around. This feels more natural for the user, as it replicates the natural movement of your body while walking or running, making the disparity between the real and virtual world smaller.

Is VR here to stay?

VR hasn’t been commercially successful yet, and this is due to Virtual Reality sickness as well as many other similar factors. Once these have been overcome, both the price and the appeal of Virtual Reality will increase, and so I believe that we will see a massive growth in use in both leisure and industry in the next few years.

No matter what happens to VR in the future, it is evident that it has had a lengthy past, and that it has come far since the first examples of creating a false reality. I hope that this can be replicated in its future and that the technology will be improved to a point where it can be incorporated into our daily lives.

Malachai Jacobs, The Bishop’s Stortford High School

Sources

https://www.vrs.org.uk/virtual-reality/history.html

https://virtualspeech.com/blog/history-of-vr